Food loomed large in my life from a very early age. For that I must chiefly thank (or blame) my mother, an excellent cook who managed to produce culinary wonders with the simplest of ingredients. Evacuated to Wakefield (Yorkshire) as an infant for part of the war, I was stuffed with stodgy pastries by the hard-working local women. Despite that, I never developed a sweet tooth, so when sweets came off rationing in 1953 I didn’t join the bevies of young children who took confectioners by storm. Instead, I was lucky enough to taste good French food during my annual visits to my French godmother in Paris. She was a film producer and left me for most of the time in the capable hands of her live-in maid, Marguerite, who was from Savoie. Marguerite, noting my greed, born of wartime deprivation, liked nothing more than making a six-egg omelette, eating a small corner of it herself, and urging me to finish the rest. Up to that point in my life, eggs were either powdered or preserved in isinglass, and I vividly remember even now their unpleasant ‘strawy’ taste. In France, eggs came off rationing relatively soon after the war, partly because of the very large population of egg-producing farmers. So an omelette (of whatever size) had the genuine eggy taste.

About

My mother, who had holidayed several times in France, made straightforward French cuisine at home, and made lavish use of such ‘exotic’ ingredients as garlic, to the bemusement of school chums I invited round and the disgust of my paternal grandmother if she was aware that garlic had gone into her food (most of the time my mother kept quiet about that, and grandma would pronounce the dish delicious).

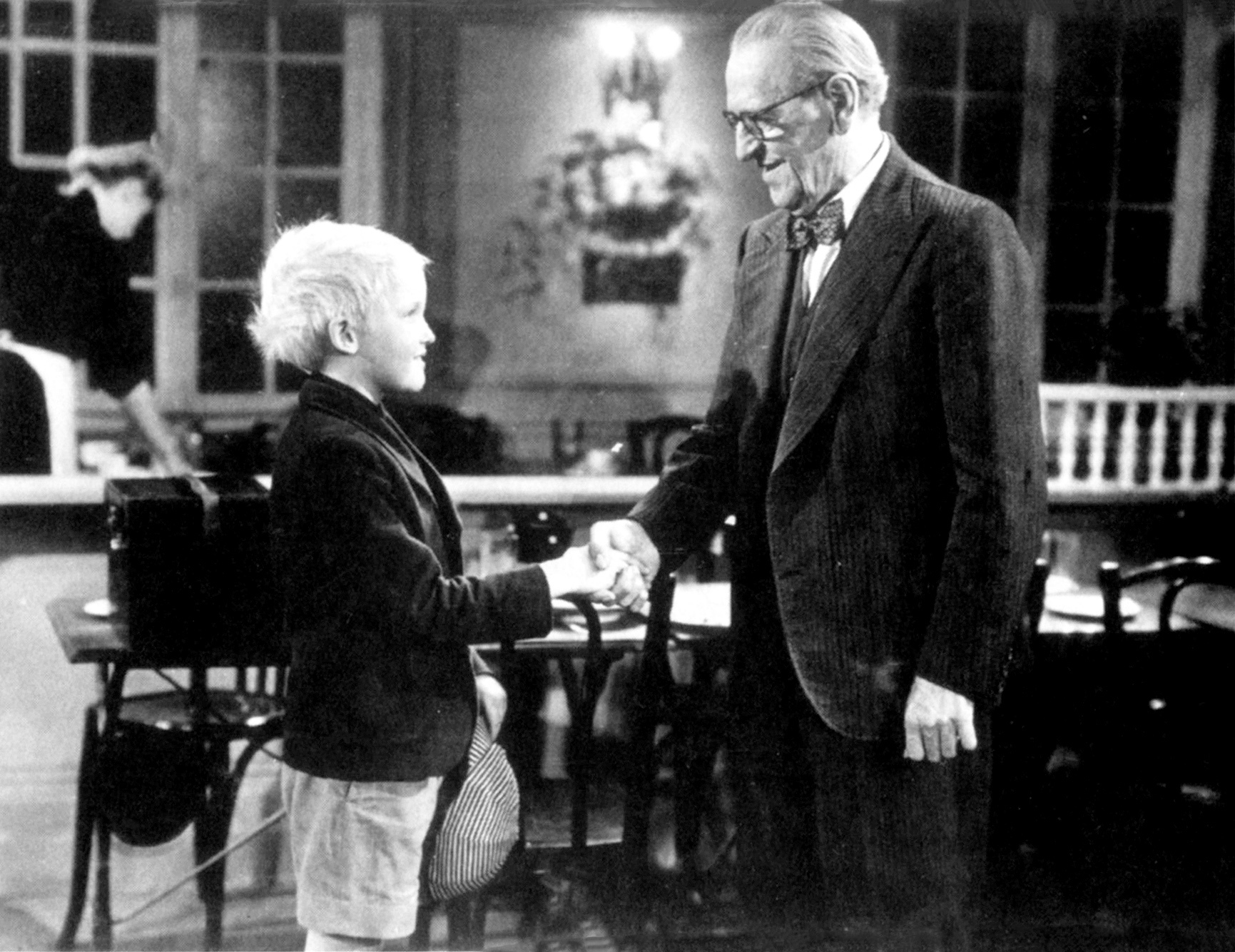

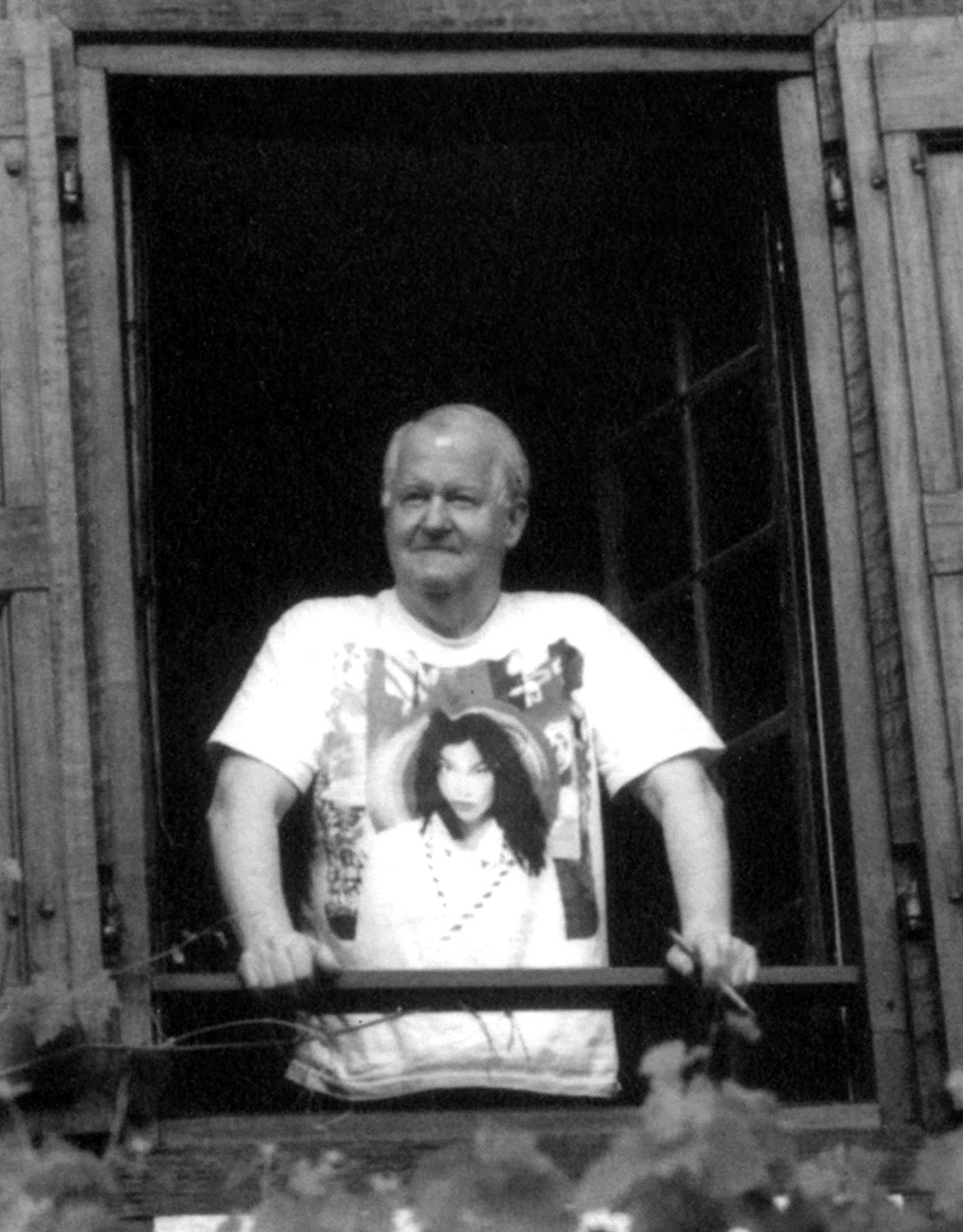

The other feature of my life has been film – no doubt because my godmother gave me a small part, as ‘Lord Peter’ (!), in Au revoir, Monsieur Grock, an unremarkable biopic she produced about the celebrated clown, Grock (1880-1959). I spent a great deal of time hanging around Paris studio lots waiting to be called on set. Although, then aged nine, I was bored most of the time, I was bitten by the film bug. After reading classics at King’s College Cambridge and being invited to take up an academic career (I’d become quite an expert on Greek particles), I decided instead to emigrate to France immediately after graduating in the hope that my godmother would get me into film-making. While at Cambridge I’d co-directed with Shama Habibullah (Waris Hussein’s sister) an undistinguished and derivative film about a freshman coming to terms with loneliness. Once in France, I made a medium-length documentary on Edith Piaf, which was followed by Gunpoint (which can be viewed in full on YouTube), a short film on the organised massacre of tame pheasants in Sologne. Film remained a central concern: I compiled A Dictionary of the Cinema (Tantivy; 1964 and 1968) and wrote The New Wave: Critical Landmarks (Secker & Warburg, 1968; an enlarged second edition, The French New Wave, was published by Palgrave in 2009, with a contextualised introduction by Professor Ginette Vincendeau). I contributed film reviews and film festival reports to the Guardian, the Sunday Times and Films and Filming.

But I continued to take a keen interest in the subject of food and wrote on food, wine and restaurants for the International Herald Tribune, the Sunday Times Magazine, the Guardian and various other publications. I suggested to Penguin that I translate Jacques Médecin’s La Cuisine du comté de Nice into English. Following an enthusiastic reader’s report by Elizabeth David, Penguin published the book as Cuisine Niçoise in 1983. I have since translated five other books on a wide variety of subjects, ranging from art, film and the history of psychoanalysis to a biography of Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the Portuguese consul in Bordeaux who, in 1940, saved the lives of thousands of Jews by signing visas allowing them to leave France for neutral Portugal.

I next suggested to Penguin that I should write a book about cheese. The response was that the market was already swamped with books on cheese, but that a book of cheese recipes would be a good idea. I imagined that the number of recipes calling for cheese must be quite small – mistakenly, as it turned out. My Classic Cheese Cookery, a chunky 401pp paperback, was published in 1988 and won the André Simon Memorial Prize.

On moving to the southern Massif Central of France in 1978 I became very interested in the cookery of the Auvergne. After extensive research in libraries and interviews with local restaurateurs and farmers’ wives, I wrote Mourjou, the Life and Food of an Auvergne Village (Viking; 1998). Somewhat to my surprise, a French literary publisher founded by Jean Cocteau, La Table Ronde, decided to have the book translated into French (by me). It came out in 2000 as Mourjou, traditions et recettes d’un village d’Auvergne.

As for the contents of this website, which will contain illustrations by the late Peter Campbell (who was responsible for the evocative line drawings used in the English edition of my Mourjou book), entries will vary in length from a few lines to several pages. They will in some cases include recipes. They will reflect my enthusiasms (for tarte Tatin, for example) and aversions (to Big Macs), and range in tone from celebration to rant. I will draw on my experiences as a restaurant critic and my encounters with professional chefs. My interest in the etymology and origins of food-related terms will become apparent. For example, the French and Italian words for a sow are truie and troia respectively: they both derive from the ancient city of Troy. I shall explain how. Doughnuts in French and German – pets de nonne and Nonnenpfürzen respectively – both translate literally into English as ‘nun’s farts’, sometimes Bowdlerised to ‘nun’s puffs’: why? As far as possible, I shall give false etymologies a wide berth.

I would naturally be delighted to receive any useful feedback, whether critical or positive, from the online community. So please fire away!