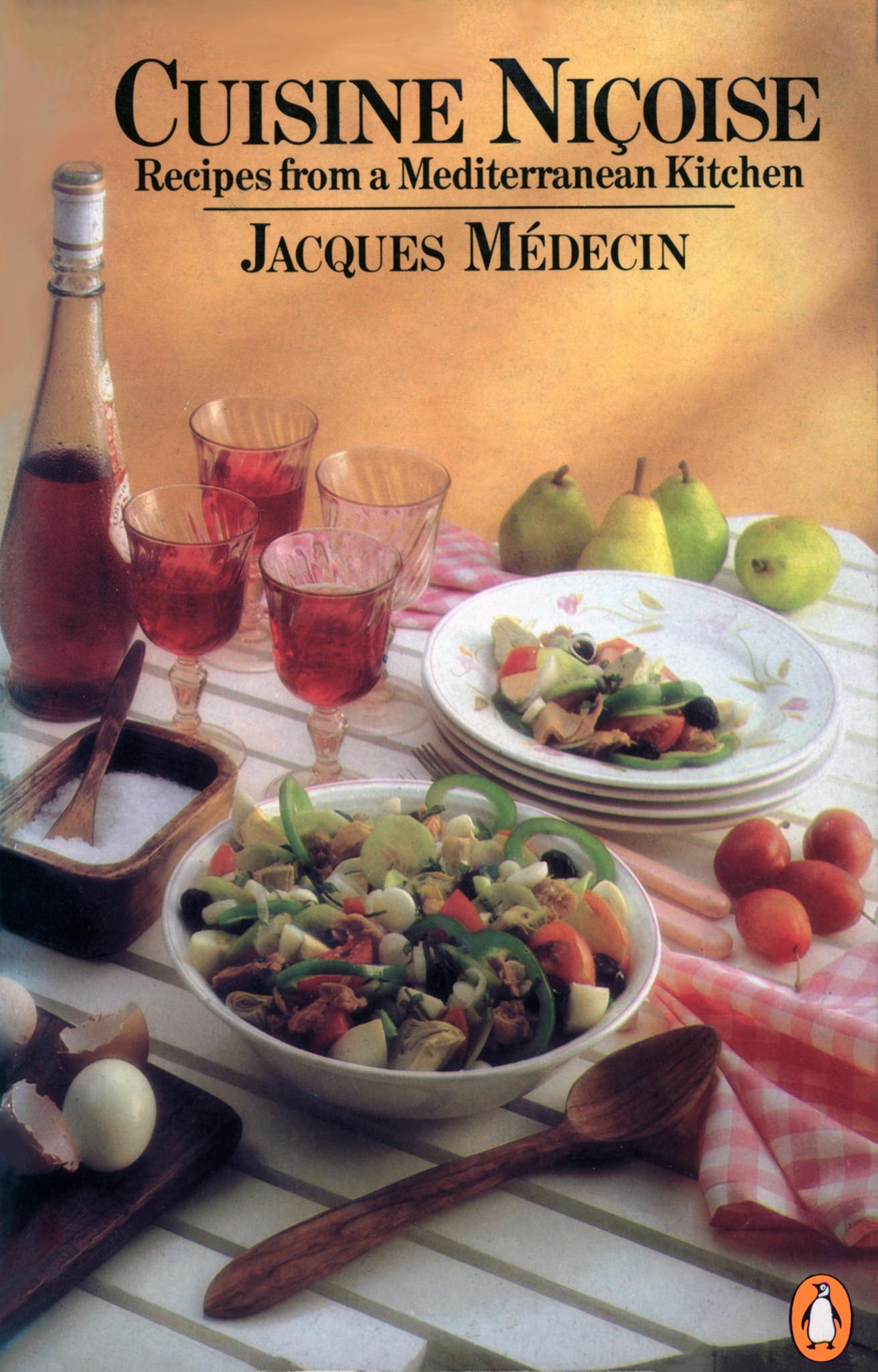

In the early 1980s, Jill Norman, pioneering cookery editor at Penguin Books, approached me to see if I might be interested in translating La Cuisine du Comté de Nice, by the mayor of Nice, Jacques Médecin. The book had been warmly recommended to her by Elizabeth David, arguably the best-known British food writer on French and Italian cuisine. I immediately accepted the offer, for Médecin’s book struck me as both mouth-watering and original. My translation was published in 1983 as Cuisine Niçoise, with the subtitle Recipes from a Mediterranean Kitchen. The reason Jill and I steered clear of the word French was simply that Nice has been part of France only since 1860. For almost 500 years before that (apart from a brief interlude under French rule from 1792 to 1814), Nice belonged to the House of Savoy, whose kingdom, known as the Kingdom of Sardinia, also included Savoy, Sardinia and Piedmont (and, for part of the mid 19th century, almost the whole of Italy). Until 1860, there was little or nothing French about Nice’s culture. And its culinary traditions, although showing some Provençal and Italian influences, have always been quite individual.

To the modern mind, Nice may conjure up an image of pleasure-seeking Edwardianism. As far as its cookery is concerned, any such image is quite irrelevant. The Promenade des Anglais, the gingerbread Hôtel Negresco, the casinos and the swish suburbs of Cimiez are mere accretions that have made their appearance only over the last 100 years or so, thanks to the attractions of sun and an average annual temperature of 18°C. They have little to do with the forces that made traditional Niçois cookery what it is.

Jacques Médecin (1929-98) was the last of a dynasty of politicians who ruled Nice for over a century. Following in the footsteps of his departmental councillor father, Alexandre Médecin (1852-1911), Jean Médecin (1890-1965) was mayor of Nice from 1928 to 1962, with a two-year hiatus towards the end of World War II following his collaborationist activities. His son, Jacques Médecin, succeeded him in 1966.

Although clearly a gourmet and a vigorous champion of all things Niçois, Jacques, known to his friends as ‘Jacquou’, admits in the preface to his book that the bulk of the ‘centuries-old’ recipes it contained had been taken down by his grandmother from an aged peasant woman, Tanta Mietta, whose touching, rather faded photograph features in the French edition of the book.

In the course of translating La Cuisine du Comté de Nice, it became clear to me that the French edition had been poorly copy-edited and that I would need to quiz Médecin himself on a number of issues (almost 100) arising from it. He gave me an appointment in the grandiose municipal chamber of the Niçois city hall. A tall, imposing and apparently affable man, Médecin wanted to give his book an air of authenticity by indicating the Niçois name of this or that plant or vegetable. In each case, I needed to know its precise name in French or English, if it existed, or at best Linnaeus’s nomenclature. Médecin was unable to supply this information. I then ventured to ask him how he could have called for the use of cinnabar to lend a rosy colour to his recipe for preserved anchovies, when cinnabar (mercury sulfide) had already been certified as a poison in many countries and banned from culinary use for over a century. Médecin was so startled he almost choked on the lunch he had been served on a tray. And surely, I asked, the amount indicated (1.5 kg of cinnabar for 1 kg of anchovies) must have been a misprint for 1.5 g. I could sense that Médecin was beginning to bridle at my questions, and after a healthy swig of Bellet wine – none of which was offered to me – he brought our interview abruptly to a close.

But not before inquiring how much I was going to be paid for my translation. I told him. ‘That’s absolute peanuts! Why don’t you let me take charge of the English version and give you a proper fee?’ ‘But I have already signed a contract with Penguin,’ I protested. ‘Oh contracts, contracts... They don’t matter.’